Soils support life

It allows plants like rice to grow upright and turn towards the sun. It also provides needed nutrients to ensure enough yields, and store and supply water to plants. It is estimated that 99% of the food and fiber we produce grows on soils and only 10-12% of the earth's surface is covered by soils available for agriculture. It helps filter water; immobilize many toxic substances, mineralize crop residues and store carbon, and exchange gases with the atmosphere.

Although these nutrients already come from the soil, some plants like rice may still need supplemental nutrients (those added to the soil with fertilizers) especially when higher yields are required for a growing population.

IRRI works on four areas that encompass soil and rice, including managing of nutrients to ensure maximum benefits for all.

Site-specific nutrient management (SSNM)

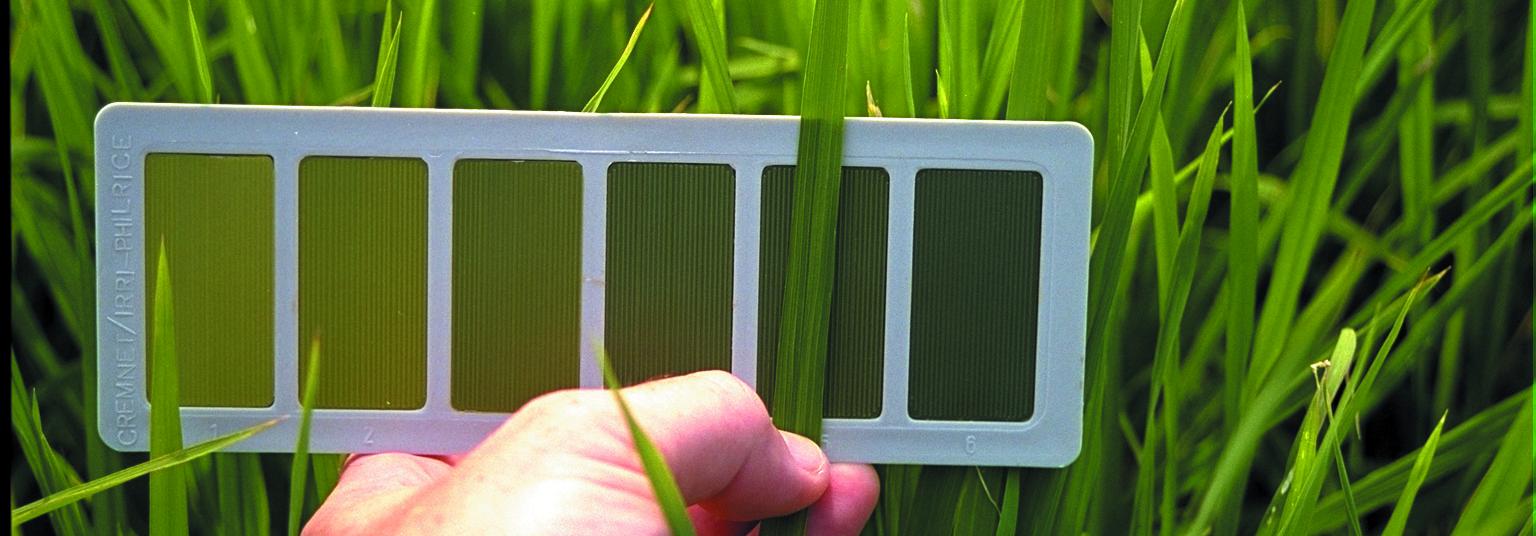

SSNM is an approach that allows rice farmers to tailor their nutrient management to the specific conditions of their field and provides a framework for best management practices for rice. It aims for efficient nutrient use by rice, and hence, help the farmer obtain high rice yields, translating to high cash value of the harvest per unit of fertilizer invested.

In 2008, emphasis was placed on providing extension workers, crop advisors, and farmers with appropriate tools to quickly develop and implement best management practices to suit specific rice-growing conditions.

This led to the development of Nutrient Manager for Rice and more recently Crop Manager, a web-based decision support tool that provides farmers with field-specific recommendations for profitable crop and nutrient management.

Microelements

Organic materials can reportedly improve a soil’s physical properties leading to better structure, aggregation, improved water-holding capacity, and better drainage. However, these changes may not do much to the flooded rice soils in Asia where fields are typically flooded during land preparation by plowing or rotovating and then tilling at soil saturation (called puddling) which eventually destroys soil structure.

Incorporated or surface-applied organic materials could potentially improve the physical properties of rice soils in cases where soil is prepared without puddling like direct dry seeding. In these cases, the potential effects on soil physical properties will depend upon tillage practices and the decomposition rate of the added organic material.

Those that are most effective as nutrient source for crops would have high concentrations of essential nutrients and relatively rapid rates of decomposition which can lead to an almost synchronized release of plant-available nutrients to coincide with the needs of the rice plants.

Micronutrients are elements that are essential for plant growth, but are only required in small quantities. They include zinc, manganese, iron, copper, and several others. There is at least a small amount of these elements present in all soils, and often there is no need to add them to achieve healthy plant growth. However, there are two general cases in which it is helpful to add them: 1) when other soil components interact to make a micronutrient unavailable for plant uptake; or 2) when plant yields are very high (due to optimum management of macronutrients and mitigation of common crop growth constraints) so that large plants are using up the small amount of micronutrients available in the soil.

For irrigated rice systems, zinc is the most common micronutrient deficiency while iron is the most common micronutrient toxicity. This is because flooding the soil causes biochemical changes that make zinc less available, while iron becomes more available to rice plants. It is possible to partially mitigate both of these micronutrient problems by carefully allowing the soil water level to go about 10 cm below the soil level for a short amount of time (5-10 days) prior to re-flooding. Another strategy to deal with these micronutrient problems is to breed varieties that are tolerant of their constraints.

A third strategy to deal with zinc deficiency is to add zinc-containing fertilizers to the soil. However, it is very difficult for rice growers to identify or predict zinc deficiency in their fields because it tends to be very specific to the site and the season. Because zinc fertilizer is much more expensive per kilogram than NPKS fertilizers, it is not profitable for growers to apply zinc if they are not sure it is necessary. Also, some of the same biochemical processes that cause soil zinc to become less plant-available after flooding also occur with applied zinc fertilizers. In other words, a grower may apply a zinc-containing fertilizer to a rice field without having any effect because the zinc from the fertilizer turned in to an unavailable form before the plant could use it. Our research is focused on helping growers identify when it is necessary to add zinc and to provide recommendations about the best way to apply it so that it stays available to the rice plants.

Zinc is also an important micronutrient for humans. Read more about our work on high-zinc rice varieties and how we help improve human nutrition.